STRUCTURES Blog > Posts > From Symmetries to Conservation Laws: A Journey with Noether's Theorem (Part I)

From Symmetries to Conservation Laws: A Journey with Noether's Theorem (Part I)

Why is energy conserved in isolated physical systems? What ensures that a planet remains in a fixed orbital plane around its star? Part of the answer lies in a simple yet profound idea: symmetry. Symmetry is one of the most fundamental and unifying principles in nature. It shapes our understanding of physical systems, from the motion of celestial bodies to the behaviour of subatomic particles. Beyond physics, symmetry has also inspired rich and elegant developments in mathematics, particularly since the 19th century.

What is Symmetry?

At its core, the idea behind the word symmetry (regardless of the precise definition) is invariance under a transformation. That is, a system is said to possess a symmetry if its essential properties or governing rules remain unchanged when a specific transformation is applied. Take an equilateral triangle, for instance: you can rotate it by 120°, or reflect it across one of its mirror axes, and it remains indistinguishable from its original state. These operations are symmetries of the triangle because they preserve a key characteristic: its shape.

More generally, any transformation that leaves an object, system, or quantity unchanged can be called a symmetry. Beyond geometric shapes, this idea applies to a wide range of contexts – from mathematical equations to physical quantities and even the laws of nature themselves. To describe the full set of symmetry transformations associated with a given object or system, scientists use the mathematical concept of groups, developed in the 19th century by mathematicians Évariste Galois and Arthur Cayley.

Groups can be thought of as collections of operations that can be combined and reversed. More precisely, they are abstract mathematical structures that follow specific rules, making them especially well-suited for capturing the essence of symmetry.

A group is a set of transformations that can be combined, such that the following properties hold:

-

Closure: Combining any two transformations in the set results in another transformation that is also in the set. Example: rotating an equilateral triangle twice by 120° is equivalent to a single 240° turn, which is also a symmetry of the triangle.

-

Identity element: There exists an identity transformation that leaves the object unchanged. In other words, “doing nothing” is a valid transformation within the group. Example: rotating by 0° is a symmetry.

-

Inverse element: For every transformation, there is another that undoes its effect. Example: rotating by 120° can be undone by rotating by -120°.

-

Associativity: The way transformations are grouped when combined does not affect the final result, as long as the order of operations remains the same. Explicitly: applying transformation C, then the combination of B and A, gives the same outcome as applying the combination of C and B, followed by A.

Note that the order in which transformations are applied can matter. For example, flipping an object and then rotating it typically yields a different result than rotating it first and then flipping. Groups in which the order of operations does not affect the outcome are called commutative or Abelian groups.

The World of Groups

Because groups are such a fundamental concept, they appear almost everywhere. They arise, sometimes in disguise, across virtually every branch of mathematics, and also in physics, chemistry, and any domain where the idea of symmetry, broadly interpreted, plays a role.

For instance, the set of integers forms a group under addition. The sum of any two integers is always another integer (closure). There is a special element (0) that leaves any number unchanged when added (identity element). Every integer has an inverse (its negative) that cancels it out, e.g., adding 5 can be undone by adding -5 (inverse element). And addition is associative: the sum a+(b+c) equals (a+b)+c (associativity). This group captures a familiar kind of symmetry: discrete translational symmetry. It models situations where a pattern can be shifted in a fixed direction (by adding a constant to all coordinates) without altering its appearance.

In the same way, the set {-1, 1} is a commutative group under multiplication. Can you see how the properties above are satisfied? Do you know what symmetry this group represents?

Hint: it is one we already encountered above.

Continuous vs. Discrete Groups

Symmetries in Physics: Preserving the Dynamics

To explore the pivotal role that symmetries play in physical systems, let us consider an example from classical mechanics.

Imagine an object moving along some trajectory through space – for instance, a swinging pendulum or a planet orbiting a star. At any given moment, the state of such a system is fully described by two sets of variables: its positions and momenta. The positions (more precisely, generalized coordinates) specify where the system is located, while the momenta (mass times velocity) specify the direction and speed at which these positions are changing. Together, these variables define what physicists call the system’s state. Moreover, the collection of all possible states of the system forms its phase space.

To better grasp the idea of phase space, think of a point particle in 3D. Normally, we track its position using three coordinates (x,y,z). To fully capture its state, though, we need to also specify the value of its three momenta (px,py, pz). We can think of these six numbers together, as the coordinates of a point in a six-dimensional landscape of all possible states of the particle: the phase space. The phase space can be seen as a geometric space like any other. In general, its dimension is twice the number of independent coordinates in the corresponding mechanical system, which are also called degrees of freedom. A pendulum hung on a thread and swinging in a plane has just one degree of freedom, so its phase space is two-dimensional. A system of two point particles in 3D has six degrees of freedom (three for each particle), thus the phase space is of dimension 12. Over time, the evolution of the mechanical system traces a path through phase space.

In classical mechanics, Newton’s second law,

Force (F) = mass (m) × acceleration (a)

describes how an object responds to applied forces. This relation determines the dynamics of the system: it dictates how the system evolves over time. For example, it explains why a ball falls to the ground when thrown in Earth’s gravitational field. In this view, Newton’s law governs not just motion in physical space, but also the trajectory that the system traces out in phase space – that is, which states it visits in time. Out of all conceivable paths through phase space, nature selects those that satisfy the dynamical laws. We will refer to such a trajectory as a physical path.

Hamilton's Principle and Dynamics of Fields

The dynamics of a physical system in phase space can be elegantly reformulated using Hamilton’s principle of least action. According to this principle, there exists a quantity called the action, which is associated with any path in phase space. Among all possible paths, the physical paths are those that minimize – or more precisely, extremize – the action locally within the space of all possible paths in phase space.

Hamilton’s principle is more general than Newton’s second law, as it remains meaningful even in contexts where Newtonian mechanics does not apply – most notably, in the realm of field theories. Fields are ubiquitous in nature, with familiar examples including the electromagnetic field and gravity. In fact, as we will explore in Part II of this blog post series, fields take centre stage in the modern framework of quantum field theory.

Broadly speaking, a field is an object that assigns a quantity to every point in space (and possibly time). This quantity could be a number – such as the temperature at each point in a room – or a vector, such as the gravitational field pointing toward the centre of the Earth. More complex fields may involve other mathematical structures. In the case of temperature, a field theory describes the dynamics of the field itself, rather than the dynamics of particles moving through it.

In field theories, the role of coordinates is taken over by field values, and momenta are replaced by the rates of change of these values. Apart from this shift, the phase space formalism applies in much the same way as in particle mechanics. Crucially, Hamilton’s principle of least action continues to hold, making it a unifying principle across both particle dynamics and field dynamics.

Having introduced phase space and the notion of “physical” paths – those singled out by the dynamical laws governing a system – we can now clarify what symmetry means in classical physics. In this context, a symmetry is a transformation acting on the coordinates (or fields) of the system in a way that preserves its dynamics. Crucially, if a given path through phase space is physical, then the transformed path must also be physical. In other words, symmetries map physical paths to other physical paths.

This may sound abstract, so let’s consider a concrete example. As mentioned earlier, a transformation can be any change applied to the coordinates or fields. Returning to the example of the integers under addition, a simple transformation would be to add a constant shift to all coordinates. If this shift does not affect the system’s dynamics – that is, if the equations of motion remain valid – then it qualifies as a symmetry transformation. For instance, imagine sliding an entire physics experiment from one side of a room to the other. If the laws of motion operate identically in both locations, this spatial shift is a symmetry. The same logic applies if you rotate the experiment or perform it at a later time. While these operations may seem trivial, they reveal something profound: technically, you are describing different systems (they occupy different regions of phase space). Yet, due to symmetry, they behave identically. Symmetries allow us to treat such differences as physically irrelevant in many contexts – which is why we often consider them “equivalent.” Formally, these transformations form groups (either discrete or continuous) that act on the mathematical structure of the system’s phase space. Understanding how these groups act on the coordinates or fields is key to uncovering deep physical principles, as we will see shortly when discussing Noether’s theorem.

In addition to their descriptive role, symmetries can also be viewed from a more practical perspective: as tools for generating new physical evolutions from known ones. As we’ve just seen, symmetries transform physical paths in phase space into other physical paths. This means that two different theoretical descriptions – related by a symmetry – correspond to the same underlying dynamics and make the same physical predictions. In this sense, symmetries establish a relationship between phase space trajectories that are dynamically equivalent. They allow us to construct entire families of solutions to the equations of motion by transforming known solutions.

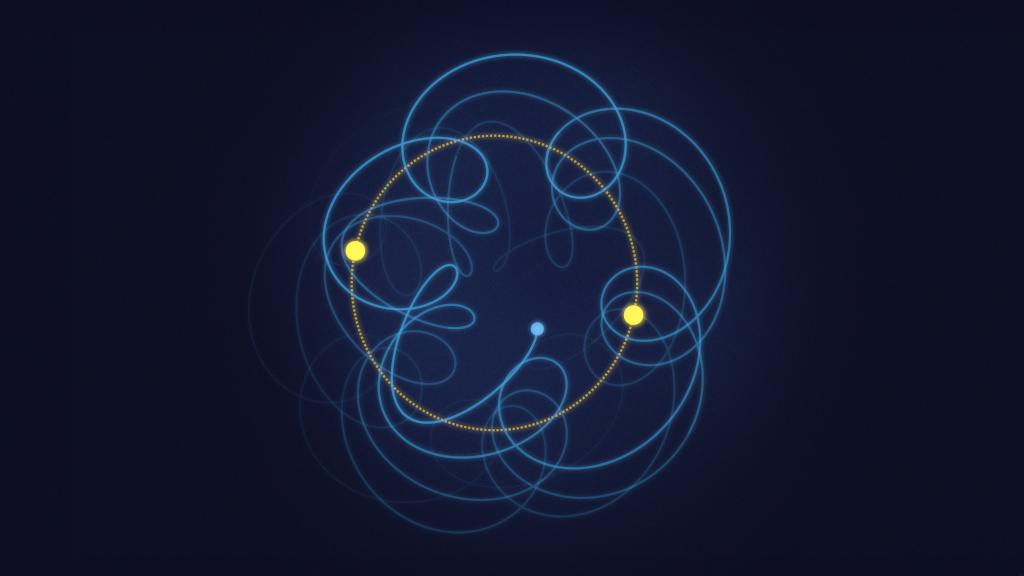

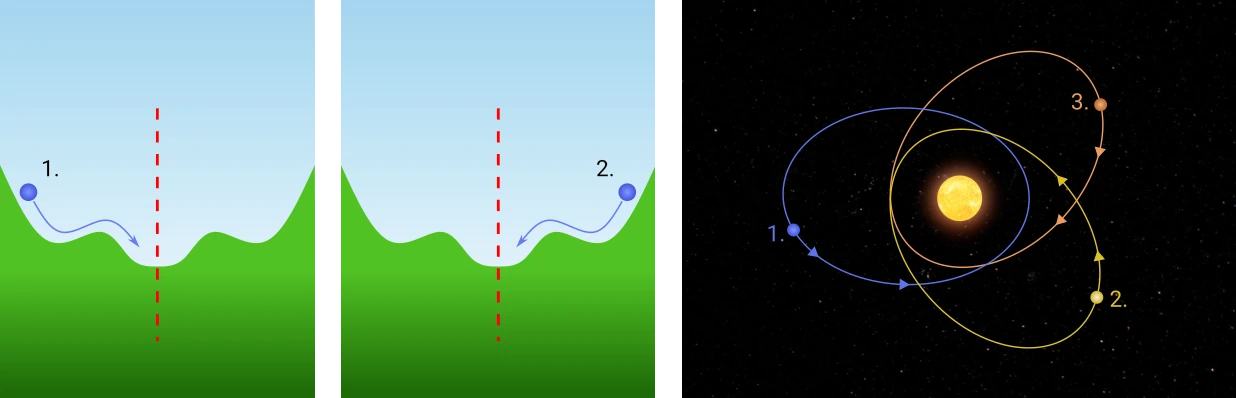

Two concrete examples are illustrated in Fig. 4. On the left, we see a marble rolling down a hill that is symmetric under reflection about its central vertical axis. Reflecting the entire setup across this axis – including the marble’s trajectory – does not change the dynamics. An observer standing on the opposite side of the hill (from our viewpoint) would perceive the mirrored version of the same physical evolution: since the laws of motion remain unchanged under this reflection, the mirrored trajectory is dynamically equivalent to the original.

On the right of Fig. 4, we see a planet orbiting a massive star in a fixed plane. Here, the key symmetry is rotation. Trajectory 2 is obtained from Trajectory 1 by rotating it around the central star. Because the star’s gravitational field is spherically symmetric – that is, it looks the same in every direction – this rotation has no impact on the physical predictions. The two trajectories are thus related by a symmetry transformation and represent equivalent physical evolutions. By rotating Trajectory 1, we’ve used the rotational symmetry to generate a new, but dynamically indistinguishable, scenario. There is another symmetry at play in this example: reflection. Can you see how applying a reflection to Trajectory 1 yields Trajectory 3?

Symmetries like these are not only conceptually powerful but also practically useful. In many areas of physics – particularly in field theory – applying a symmetry transformation can simplify the formulation of a problem or help generate new solutions from known ones. Often, a complicated system can be reduced to a simpler one by identifying symmetry-equivalent points in phase space. Insights or results obtained from the simplified system can then be transferred back to the original, more complex setup – a strategy that lies at the heart of many powerful techniques in theoretical physics.

From Symmetries to Conservations Laws

In the previous example of the planet orbiting a star, you may have noticed that the image depicts what is known as a Kepler ellipse. This is the characteristic elliptical orbit predicted by the dynamics of a simple two-body system: a single planet orbiting a massive star. A remarkable feature of this motion is that it conserves two key quantities: energy and angular momentum. Both remain constant along any physical path in phase space, which we take as the definition of a conserved quantity.

The existence of such conserved quantities is important for two reasons. First, they significantly simplify the analysis of a system – the more conserved quantities one identifies, the more constrained it is and the easier it becomes to understand its dynamics. Second, conserved quantities offer deeper physical insights. For example, if orbital energy is conserved, the sign of the energy alone tells us whether an object will remain bound to the star or escape its gravitational pull.

This naturally raises a deeper question: Why do conserved quantities exist in the first place? Is there a unifying principle behind them? Remarkably, the answer is yes – and once again, it involves symmetry. More specifically, it involves the special class of continuous symmetries we discussed earlier.

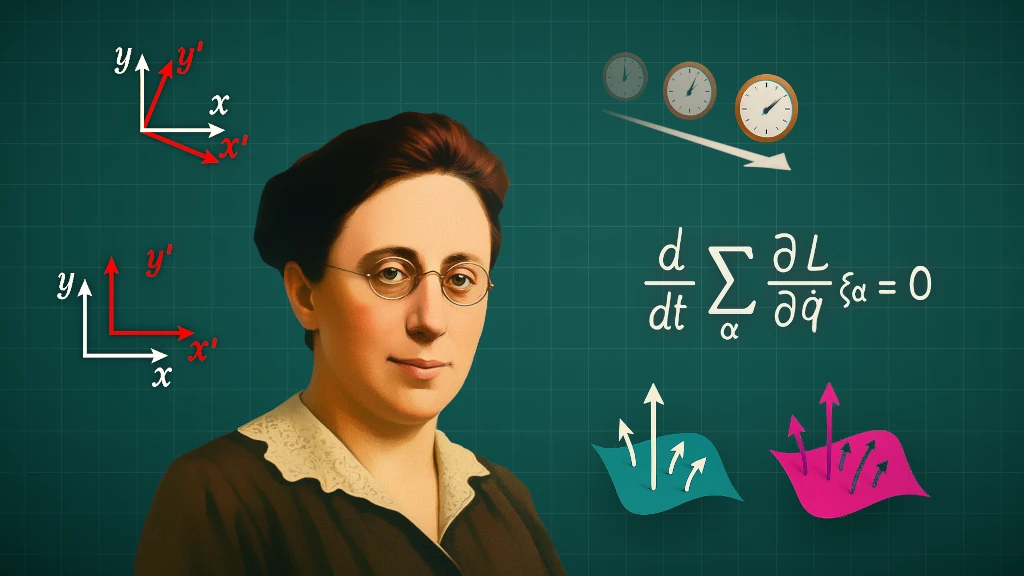

In 1918, the brilliant mathematician Emmy Noether made a groundbreaking discovery that revealed a deep connection between symmetry and conservation. At the time, she was working in Göttingen, informally lecturing under a male colleague’s name because, as a woman, she was barred from holding an official academic position.

Noether's Theorem

(Emmy Noether, 1918)

This profound result, now known as Noether’s theorem, is a cornerstone of modern physics1.

How can we understand Noether’s theorem?

We have already encountered two examples of continuous symmetries in physical systems: translations and rotations. Noether’s theorem states that if the dynamics of a system remain invariant under such transformations, then there exist corresponding conserved quantities. More than that, Noether’s theorem provides a systematic way to derive these conserved quantities directly from the symmetries.

Many familiar conservation laws in physics correspond precisely to symmetries of the underlying dynamics. For example:

- Spatial translation symmetry: If a physical system is invariant under arbitrary shifts in space then Noether’s theorem tells us that momentum is conserved along physical trajectories in phase space. In other words, momentum is a constant of motion.

- Time translation symmetry: If the laws of physics do not depend on the specific time at which an experiment begins, then there is a corresponding conserved quantity, which is nothing else than energy.

- Rotational symmetry: If the dynamics of a system remain unchanged under continuous rotations, then angular momentum is conserved during its evolution.

But why are conservation laws so fundamental, and how does Noether’s theorem deepen our understanding of them?

How Conservation Laws Rule the World of Physics

Even before Noether proved the theorem that now bears her name, conservation laws were already known to play a fundamental role in the mathematical description of physical systems. For example, the conservation of momentum and energy was central to the development of celestial mechanics, with significant contributions from many renowned mathematicians and physicists, including Galileo Galilei, Gottfried Leibniz, Isaac Newton, Johann and Daniel Bernoulli, and Émilie du Châtelet.

Noether’s groundbreaking contribution was to reveal a deep connection between conservation laws and symmetries, which she identified as their underlying source. Her theorem transformed the search for conserved quantities into the study of a system’s symmetries, providing physicists with a systematic and powerful tool for uncovering them. Conversely, the presence of conserved quantities can also signal underlying symmetries. For example, the fact that planetary orbits remain stable as time goes by suggests that the governing physical laws are invariant under time translations.

Noether’s theorem extends far beyond classical mechanics. As mentioned above, it applies equally well to classical field theories, where the phase space is infinite-dimensional. Moreover, Noether’s theorem has a quantum analogue in the form of the so-called Ward-Takahashi identities, which play a central role in quantum field theories. These identities encode the consequences of symmetries in the quantum world, where conserved quantities remain meaningful even in the presence of quantum fluctuations.

Outlook and Conclusion

In this first part of this series of blog posts, we explored the concept of symmetries and their crucial role in classical physics, rooted in their deep connection to conserved quantities. Discovering a conservation law is both fascinating and rewarding: it offers a broader, more universal perspective on a physical system. Thanks to Emmy Noether, the search for such conserved quantities transformed from a laborious and sometimes error-prone empirical endeavor into a more elegant and systematic investigation of symmetries, within a remarkably successful mathematical framework for describing classical physics. Her insight remains one of the most profound contributions to modern science.

The search for conservation laws – and thus symmetries – is a vital part of understanding a physical system at its most fundamental level. In fact, in the second part of this blog series, we will turn to quantum field theories (QFTs), which are the mathematical frameworks underlying modern particle physics. The celebrated Standard Model of particle physics, for example, is a quantum field theory. Symmetries have played, and continue to play, a central role in the development of QFTs. They are deeply connected to the very notion of fundamental forces and often serve as the “fingerprints” of a theory, helping mathematicians and physicists recognize when two seemingly different models are, in fact, equivalent. In recent years, the concept of symmetry in quantum field theory has been generalized in striking and powerful ways.

Curious to learn more? Be sure to check out Part II!

Tags:

Physics

Symmetry

Algebra

Dynamical Systems

Mathematics

Groups

Invariants